- Hybridization of wheat

- Is wheat really a wheat – Green Revolution and Gluten

Wheat products are familiar to all of us and have become an indispensable part of our diet, including bread, pasta, pizza, cookies, and cakes. In recent years, the “gluten” found in wheat flour has garnered attention and is said to be the cause of various illnesses.

Incidentally, in the United States, an average person consumes about 60 kilograms of wheat flour annually. In Japan, this amount is roughly half, about 32 kilograms per person.

Today, continuing from my previous discussion on eggs, I would like to delve into the topic of wheat, now a staple food rivaling rice for the Japanese, in a two-part series.

The History of the True Wheat

Once, Hillary Clinton, when she ran for President of the United States said, “Many ordinary people think that genetic modification is about stitching food together like Frankenstein, and we need to correct this thinking.” Wheat is not currently genetically modified for commercial use (at least not yet). Let’s dive into the history where you might surprise to know what you think wheat really is.

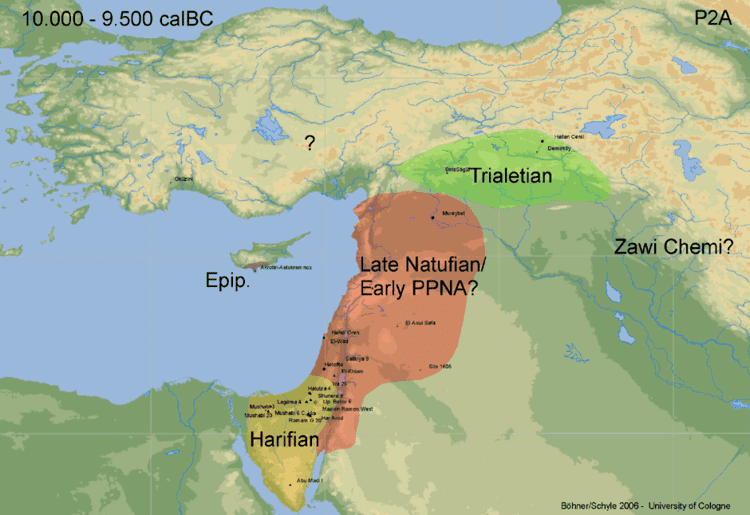

The history of wheat dates back to around 8500 BC. It existed in the Natufian culture, which spanned the banks of the Jordan River and the Dead Sea, where hunter-gatherer tribes harvested “einkorn,” the ancestor of modern wheat. This einkorn is genetically the simplest form, with only 14 chromosomes.

Subsequently, through natural hybridization, einkorn crossed with a wild grass called goatgrass (Aegilops speltoides), resulting in emmer wheat, which was mainly consumed in the Middle East. The 14 chromosomes of einkorn combined with the 14 chromosomes of goatgrass, forming a more complex 28-chromosome structure.

The wheat mentioned in the times of Moses was likely emmer wheat, which was also favored in Egypt. Wall paintings from around 3000 BC depict what appear to be bread-making recipes, showing emmer wheat being milled by hand.

Later, the 28-chromosome emmer wheat hybridized naturally with other grasses, creating Triticum aestivum, a wheat with 42 chromosomes, which is genetically close to what we now call “wheat.” This wheat is the most genetically complex, combining the 42 chromosomes from three plants. At the same time, since it became genetically complex, it became much easier for human to manipulate.

This natural hybridization remained unchanged for thousands of years, with wheat from the 17th century being nearly identical to that consumed in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries.

The Reality that Wheat is the True Frankenstein

In the latter half of the 1900s, wheat began to be manipulated by humans. The most significant cause was the “Green Revolution” initiated by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (IMWIC) based in Mexico since 1950. Norman Borlaug, an agronomist considered the father of the Green Revolution, worked for this organization and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in developing dwarf wheat, credited with “saving one billion people from hunger.”

This initiative was heavily funded by entities like the Rockefeller and Ford foundations, aiming to combat world hunger (This to me reminds me of the background of modern genetic modification – Monsanto Glyphosate+GMO).

Through this activity, new strains of wheat, such as semi-dwarf and dwarf wheat, were created, forming the prototype of the current industrial agriculture style. Simultaneously, the dependency on pesticides led to the proliferation of agricultural chemical companies, a view supported by many environmental and agricultural scientists.

Interestingly, short-stature wheat was also developed in Japan by Gonjiro Inazuka, and the hybrid of the Japanese and American versions resulted in dwarf wheat, ranging from 60 to 110 centimeters in height.

The shorter height of dwarf wheat allowed more plant energy to be used for seed production, increasing yield. However, this marked the beginning of countless hybridizations driven by commercial advantages, performed without the requirement of animal or human testing, a practice that continues today.

The issue is that no experiments have been conducted on these genetically altered plants, which now vastly differ from the original “wheat.”

Currently, 99% of the world’s wheat is this dwarf wheat, and there are over 25,000 varieties of wheat, all artificially created. And still on going.

Research to date suggests that the assumption that “crossbreeding of the same species is always safe” is flawed. For example, 5% of the proteins in these hybridized wheat differ from their ancestral species, especially in gluten composition. Additionally, one crossbreeding experiment found 14 gluten proteins in the offspring that were absent in the parents. Modern common wheat (Triticum aestivum) has been found to contain more gluten proteins associated with celiac disease compared to wheat from a century ago.

The ongoing crossbreeding from the Green Revolution focuses solely on increasing yield, ensuring the stalks don’t fall, growing in dry conditions, tolerating high temperatures, and preventing rot.

Can we still call this overly hybridized, patched-together food “wheat”? How do these Frankenstein-like wheat products, such as bread, udon, and other wheat products we consume daily, affect us?

We will explore this further in the next part.

Subscribe to “Live Your Best”, your go-to source for comprehensive information to guide you on the path to a healthier life. Drawing from my expertise as a certified Health Coach and insights from practices such as Shiatsu, Taichi-Chen, and Daoism, I will share my discoveries for health and longevity in unconventional ways.

Note: Please be aware this blog system default language is set to Japanese, the notification email you will receive may be Japanese BUT the contents are all in English.